Update: This kinda blew up! Featured in Hacker News, Ars Technica and PC Gamer, among others.

Just months after Neil Armstrong’s historic moonwalk, Jim Storer, a Lexington High School student in Massachusetts, wrote the first Lunar Landing game. By 1973, it had become “by far and away the single most popular computer game.” A simple text game, you pilot a moon lander, aiming for a gentle touch down on the moon. All motion is vertical and you decide every 10 simulated seconds how much fuel to burn.

I recently explored the optimal fuel burn schedule to land as gently as possible and with maximum remaining fuel. Surprisingly, the theoretical best strategy didn’t work. The game falsely thinks the lander doesn’t touch down on the surface when in fact it does. Digging in, I was amazed by the sophisticated physics and numerical computing in the game. Eventually I found a bug: a missing “divide by two” that had seemingly gone unnoticed for nearly 55 years.

Landing with Maximum Fuel

To use the least fuel while landing, you need to land in the shortest time possible. Initially you maximize your speed by keeping your engine off, then at the last possible second you burn full throttle, reducing your speed to zero just as you touch the surface. The Kerbal Space Program community calls this a “suicide burn”, since getting the timing right is hard and it leaves no room for error.

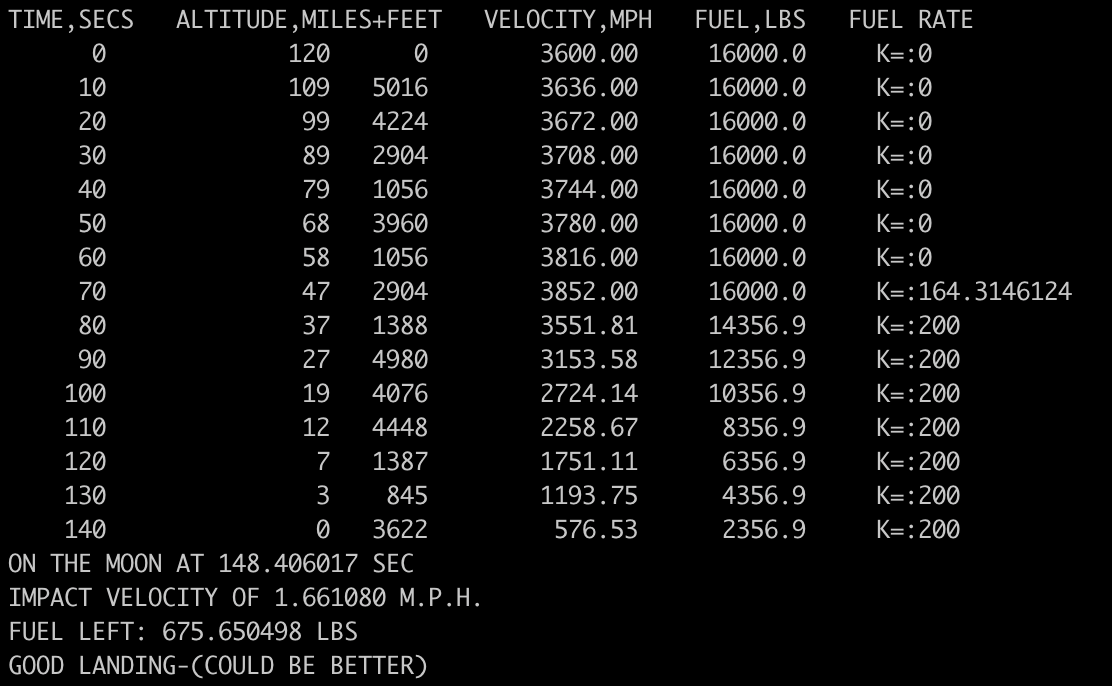

With some trial and error and a bit of (manual) binary search, you can find the schedule that just barely has you landing. You burn nothing for 70 seconds, then 164.31426784 lbs/sec for the next 10 seconds, then the max 200 lbs/sec after that:

The game considers a perfect landing to be less than 1 MPH, but here we land at over 3.5 MPH and are told we “could be better.” Yet burn even 0.00000001 more lbs/sec, and you miss the surface entirely, ascending at 114 MPH:

How did we go from a hard landing to not landing at all, without a soft landing in between?

Physics Simulation: One Smart Kid

I expected to see the simple Euler integration that’s common in video games even today. That’s where you compute the forces at the start of each time step, then use F=ma to compute the acceleration, then assume the acceleration is constant over a time step of seconds:

Because the mass is changing over the timestep, the acceleration will change too, so assuming it’s constant is only approximate. But surprisingly, Jim used the exact solution, the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, with a Taylor series expansion for the logarithm. He also used some algebra to simplify it and reduce the amount of round off error. Very impressive for a high school senior in 1969. When I asked him about it:

“I was skilled at calculus at the time and familiar with concepts like a Taylor series, but also my recollection is that my father, who was a physicist, helped me in the derivation of the equations.” – Jim Storer, personal communication

The rocket equation is what gives rise to the suicide burn being optimal, and the five terms he uses of the Taylor series, where the argument is at most 0.1212, makes it accurate to over six decimal places. So that’s not the problem we’re looking for.

Assumptions Go Out The Window When We Hit The Ground

The rocket equation works well until you hit the ground. In general, collisions between solid objects is a really hard part of dynamics engines, and what separates the great ones from the good ones, as I discovered when contributing to Open Dynamics Engine as a postdoc at MIT.

And this is where the Lunar Landing Game faces its biggest challenge. Imagine the lander descending at the start of a 10-second turn but ascending by the end. Simply verifying that it’s above the surface at both points isn’t enough. It might have dipped below the surface somewhere in between. When this happens, the program has to rewind and examine an earlier moment.

An obvious place is to look at the lowest point of the trajectory, where the velocity is zero. For the rocket equation, it turns out, there’s no closed form expression for that lowest point that involves only basic mathematical functions.1 So instead, we can use the physicists favourite technique, and take only the first few terms of the Taylor series. If you use only the first two terms of the logarithm, the problem simplifies to a quadratic equation and you can use the good old quadratic formula from high school. And the approximation should be pretty good over the space of a 10 second turn, accurate to within 0.1% or so.

But that’s not what Jim did. His formula has a square root in the denominator, not the numerator. It also had an error 30 times bigger.

How To Know When You’ve Hit Rock Bottom

What could he possibly be doing? I stared at this for a long time, wracking my brain for any other approach to approximate the bottom of the trajectory that would still only use addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and square root. Taking only the first term of the logarithm would give an approximation worse than the quadratic, but wouldn’t involve a square root. Taking a third term and we need to solve a cubic, which in general would need a lot more code and in our case it doesn’t seem to be of any special form that has a simple solution2. There are many approximations to , but the non-Taylor ones involve advanced functions like

that are hard to invert.

Until I looked a little more closely at his square root. It’s of the form:

Which looks a awful lot like the quadratic formula where we’ve divided by 4 inside the square root. It has to be related. But why is it in the denominator? Did he find a quadratic in ? No, because t can be very close to zero, so his formula would need to be approximated over a wide range of very large values, and a quadratic isn’t good for that. Did he make a quadratic approximation to log, then substitute

, solve for T, then substitute back? Playing around with that, I re-discovered an alternate form of the quadratic formula with the square root on the bottom! And indeed, this matches the formula in Jim’s code.

And this alternate form has a key advantage. Because once we discover that we’ve hit the ground, we need to go back and find the time where we hit the ground. And we do the same thing, truncating the Taylor series to give us a quadratic. And in that case, the original form has a divide by zero when the leading coefficient is zero. That happens when the thrust from the rocket engine exactly balances the force of gravity. And that’s probably common for many players, who hover over the surface and gently descend. And they don’t need to be exactly equal. If the thrust is close to the force of gravity, you can get catastrophic cancellation in the numerator, then the tiny denominator blows up your errors. This alternate form is much more numerically stable, and in fact works just fine when the quadratic term is zero, so we actually have a linear equation and not quadratic. It’s amazing to me that Jim would either somehow re-derive it, or learn it somewhere. I don’t think it’s taught in textbooks outside numerical computing, and I don’t think it’s even common in physics.

Let’s Double Check The Derivation

But if his formula is equivalent, then why is the approximation error 30 times higher? Deriving the formula ourselves, we get:

Which is identical to Jim’s code, except … he’s missing the 2 in the denominator inside the square root! It was probably a simple error, either when deriving the formula or typing it into the computer. After all, the computer algebra system MACSYMA had only started a year before, and wouldn’t be available at a high school, so he would have had to do everything using pencil and paper.

With this bug, he consistently underestimates the time to the lowest point. He compensates for this two ways: adding 0.05 sec, and then re-estimating from his new, closer location. And this explains why it misses the time of landing: the first estimate is while the lander is above the surface and still descending, then the second one is after reaching the bottom and ascending again, which takes less than 0.05 sec.

If we add the missing factor of two and remove the 0.05, what happens? Now the best we can do with a suicide burn is:

Our velocity is down to 1.66 MPH, almost three quarters of the way to the perfect landing at 1 MPH. It’s not perfect because we’re still only using the first two terms of the Taylor series. Also, once you’ve decided your lowest point is under the surface, you then need to find the time where you first hit the surface, which involves a similar approximation. Another iteration would help, although with the bug fixed we overestimate the time, so we’d need to go back in time, which might mean we have to pick the other solution to the quadratic. You could simplify that by using only a single term from the Taylor series, and is what’s done in Newton’s method. You could then stop when the magnitude of the velocity is below some threshold, and use the altitude there to decide whether or not you landed. But this is all more work, and the game was fun to play as it is, so why complicate the code?

It’s also possible to land gently, you just need to end your 14th turn with a low altitude and velocity, and then use low thrust in your 15th turn, landing somewhere after 150 seconds. It’s just the theoretical full-thrust-on-landing suicide burn, that takes around 148 seconds, that eludes us.

CAPCOM We’re Go For Powered Descent

Overall, this is very impressive work for an 18 year hold high school student in 1969 on a PDP-8. This was long before Computer Science was taught in high school. The numerical computing aspects, such as iteratively improving the estimate using Newton’s method or worrying about catastrophic cancellation, weren’t well known back then. I didn’t learn them until I was studying for a Ph.D. in robotics.

It is also surprising that, as far as I can tell, this bug has been there for almost 55 years and nobody has noticed it before. That’s probably because, even with the bug, it was a fun game, both difficult and possible to land gently. The quest to not just win, but find the optimal strategy, can certainly lead to trying to understand small discrepancies. I suspect everybody else was just happy to play the game and have fun.

- It needs the Lambert W, the inverse of

↩︎

- For example,

, where the 2nd and 3rd coefficients have the same magnitude but different sign, can be factored in the form

, which has solution

↩︎